At OCEARCH, research and conservation are at the heart of everything we do. Every expedition, partnership, and initiative is designed to generate open-source data that advances the scientific understanding of sharks and other marine species. By collaborating with world-class researchers and institutions, we not only uncover mysteries but also ensure this knowledge informs global conservation policies. Our mission is clear: to return the ocean to balance and abundance by protecting critical habitats and inspiring communities to take action for the future of our planet’s most vital resource.

COMBATING ILLEGAL TRADE OF AQUATIC WILDLIFE

With funding by the nonprofit organization OCEARCH, a new project to detect illegal trade in sharks and other marine and freshwater wildlife will provide a vital tool in the global effort to reverse the decline of vulnerable and endangered species on our planet. Led by Dr. Diego Cardeñosa of Florida International University and Dr. Demian Chapman of Mote Marine Laboratory, the development and deployment of their “DNA Toolkit” in Latin America, Europe, and Southeast Asia is a much-needed breakthrough to combat illegal trafficking in shark, eel, turtle, tuna, and other wildlife products.

The DNA Toolkit uses toaster-sized, portable units to conduct DNA testing of wildlife products, with results obtained within a few hours at a fraction of the previous cost of such work—less than a dollar per sample. In each country where this is deployed, inspection officers are trained to use the tool to identify species and incorporate DNA test results into their evidentiary record and prosecutions against wildlife smuggling and illegal trade.

With the support of OCEARCH and other grants the team has built basic DNA testing capacity in Hong Kong, Brazil, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Columbia, Belize, Sri Lanka, Mozambique and Tanzania. These are all hotpots in the shark product industry and sites of potential illegal trade. The ultimate goal is to have operation in-port PCR testing occurring at multiple locations in all major supply chains for sharks and rays products by 2030.

PROTECTING THE COCOS-GALAPAGOS SWIMWAY

In 2014 OCEARCH led an expedition in Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands with scientific collaborators MigraMar, Galapagos National Park Directorate and the Charles Darwin Foundation. During the research effort, 4 tiger sharks were caught and released and became the first acoustically tagged tigers in the region. In the years that followed the scientific team showed that the tagged tiger sharks spent most of their time within the Galapagos Reserve safe from fishing pressures, demonstrating the importance of identifying critical habitat and the role of Marine Protected Areas in shark population recovery. Remarkably, in 2017, one of the tagged tigers was detected in Costa Rica’s Cocos Islands, having traveled at least 440 miles from the Galapagos Islands through unprotected waters. This was the first recorded movement of a tiger shark between these two protected areas, and the 6th highly migratory species, including sea turtles (leatherback, green) and sharks (whale shark, silky shark, scalloped hammerhead), shown to make this trip using this same corridor. The Cocos-Galapagos Swimway is a 74,500 to 149,000 square mile area that serves as an underwater migratory highway connecting the national parks of these two nations – both of which are UNESCO world heritage sites. While each park is protected the swimway is not, making it a critical area to understand and include in building conservation strategies. Through the advocacy efforts of OCEARCH collaborating partners, Ecuador has protected its portion of the swimway; the Costa Rica portion remains unprotected and an area of ongoing championing.

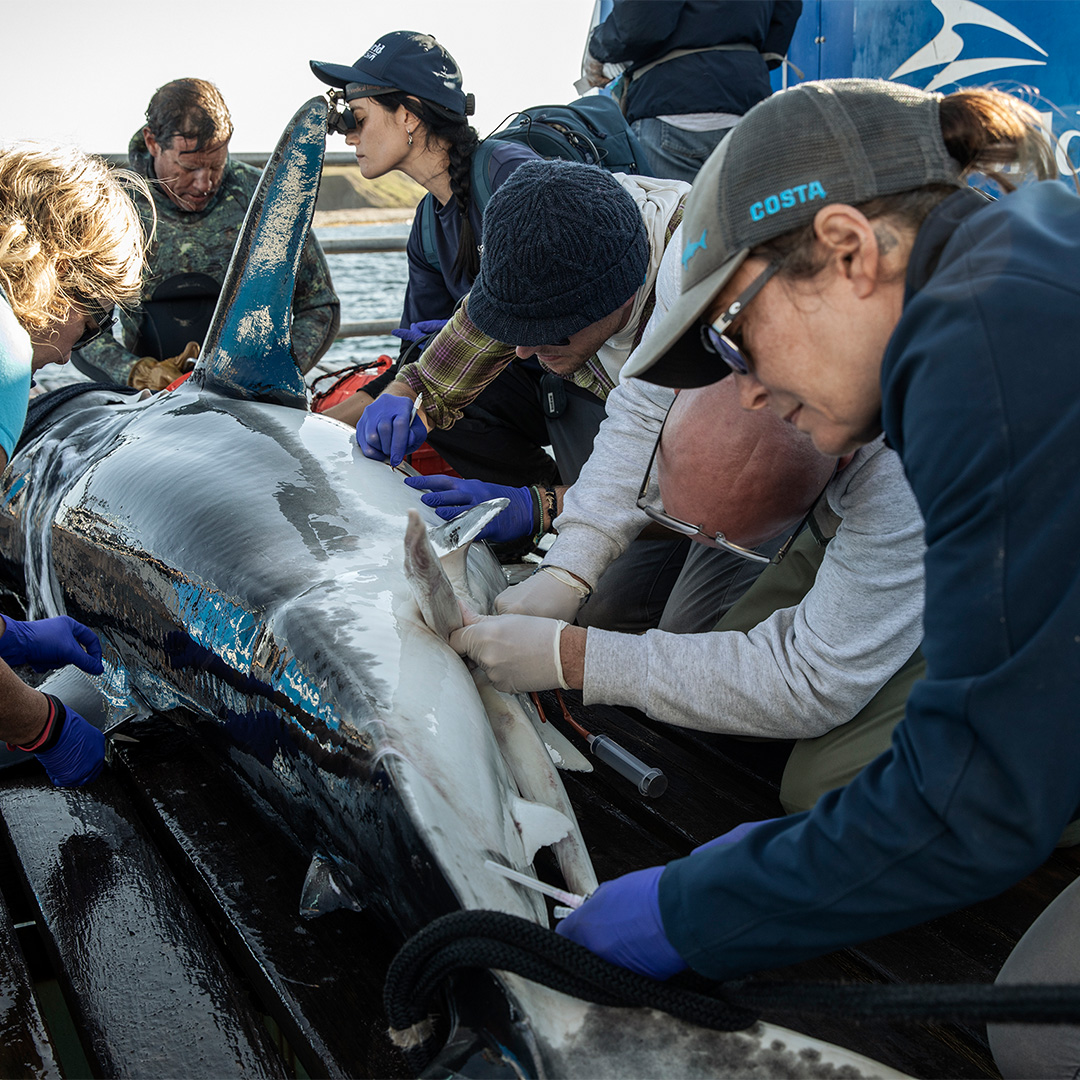

TRACKING THE ‘DISAPPEARANCE’ OF SOUTH AFRICAN WHITE SHARKS

In 2012 OCEARCH led a 48 day expedition in South Africa, resulting in the capture and tagging of 40 white sharks, facilitating collaborative research to better define and document their habitat use, migratory patterns, and life history. This lead scientists on this expedition used this baseline data to describe white shark habitat use, movements and distribution throughout the region. This became critically important between 2015 and 2018 when white shark sightings began to plummet in previous ‘hot spots’ such as False Bay and Gansbaai. A number of contributing factors are likely contributing to these declines including human induced mortality (fishing pressure, beach protection drumlines), decline in prey species (cape fur seals, small sharks and fish), and low genetic diversity. A notable contributor to their disappearance was the arrival of a distinctive pair of Orca, named Port and Starboard due to bends in their dorsal fins, in Gaansbai in 2015. Both animals were documented feeding on a variety of shark species including white sharks and since that time the number of Orca using sharks as their primary prey species in the region has increased. The presence of Orca in the region are suspected to have triggered a new distribution pattern of white sharks to locations further east, such as Mossel Bay to avoid these large predators. Without baseline habitat and movement patterns of these species the complex effects of orca, humans and other factors on white shark populations would have been difficult to document and study.